Five hours and eight cups of tea later, and I was three hours from freedom. The email server was down and the browser's progress-bar on my unclassified monitor was still stuck at fifty-percent. But I didn't care because I was too busy cursing under my breath in fake French. I'd been tweaking avionics flight software all morning and running the simulation repeatedly and the HERA unitary was still hanging on to anal virginity by a fraction of a meter. I was running out of options and the sleep deprivation was gnawing at my cognizance. The keyboard was sandwiched between my hands and the desk calendar. My fingertips felt heavy and I could feel the keys on the threshold of giving way beneath them. The desk calendar was still stuck in February. A pencil-sketched jolly-roger jeered up at me from the February 14th block. The rest of the calendar was graffiti-ed with random scribbles that looked like the underside of a Harlem overpass.

I could hear Gary talking in the hallway: "Yeah, I've seen 'em launch a CLASSIFIED from a CLASSIFIED. I was in Alaska and they had one on a CLASSIFIED. The launch crew guys were all running around in chemical suits. They take liquid propellant and the mother f%$kers leak like colanders so they have to fuel 'm half an hour before launch and the fuel is pretty caustic sh!t." I raised my eyebrows in interest as I listened. These guys were so full of useful information like that. I yawned and spun around in my chair and dug through my briefcase in search of my bottle of Ritalin. I was among the first generation of kids to be diagnosed with ADD and this was back before they quit prescribing Ritalin. I’d been taking it for over twenty years; I always joke with the pharmacist that one of these days they’re gonna drag me in to some lab to see what the drug’s long-term side-effects are. Ritalin was the only thing that kept me out of the Military Academy and as of last week, the CIA as well. Regarding West Point, I had already received the congressional nomination and I’d been awarded the appointment when they found out. I always felt pretty sh!tty about the whole thing. I’d worked damned hard for that appointment and all it took was twenty milligrams of a controlled substance to lose it. All the running, all the swimming, all the calisthenics, all of the studying for nothing. Getting into West Point had been my life. But there I was nearly a decade later, in the best shape of my life, running six-and-a-half minute miles for ten miles, swimming a twenty-minute mile, and able to crack off a dozen reps of one-armed pull-ups on each arm, and getting paid thirty dollars an hour to browse and write classified flight software. I shouldn’t have complained, but I did because it was all bullsh!t. Each and every day, I wished that I was in Iraq or Afghanistan, especially after Tracy left. I wasn’t afraid of dying.

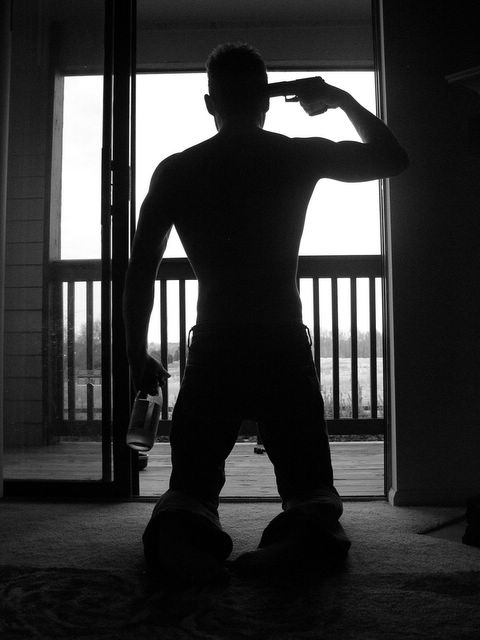

In fact, not a day had passed during my last year of grad-school wherein I’d not wrapped my lips around the business-end of that H&K and looked God in the face. In the end I could never do it because I loved Tracy too much to let her find me like that, to leave her with the debt and the mortgage. You know how they say: "You always kill the ones you love." At least that’s what Chuck Palahniuk said that they say. I wonder if Tracy knew how easily she could have killed me if she had just left me then instead of later. I lie in my sleeping bag at night sometimes and shutter when I think about how close I came and I get up and stare out at the pasture in the moonlight and I realize that I’ll never contemplate suicide again. After everything that I went through, everything came out alright in the end. Didn't it? At least that's what I told myself. But more often than not, I caught myself eyeing the H&K when I was alone in the evenings.

Surely things would never be as dark as they were aboard the Mr. John in the dark, pre-dawn hours of 02 May, 2005 after I’d driven five-hundred miles from Mobile to Auburn and back in a rental car. After Tracy's student loans came due and after I finally got fed up enough with graduate school, I'd taken a job as a field engineer for Schlumberger, an oil field services company. It was the only job that I could get, even after graduating from engineering school with honors. That's how I found myself on the TODCO 200, an old jack-up oil rig that sat out in the Gulf of Mexico about forty miles due south of Mobile Bay. They’d T-D’ed the first vertical section of the well at 0130 on 30 April and they’d sent us ashore while the casing crew went to work. I had forty-eight hours and I missed Tracy so badly and I couldn’t spend the night in Mobile knowing that I was ashore and only two hundred miles away from my wife. We landed at the wharves in Theodore at 0600 and I hitched a ride with the mud-loggers. They dropped me off at a rental car office on their way to their motel. I had to wait an hour for the office to open.

A thunderstorm had followed us in from the gulf and the morning was dark. My sleep cycle was so warped that I kept thinking that it was late evening. The rain was falling hard. Mobile rain, fresh with the briny scent of the bay. Heavy rain, that came in waves of large marble-sized drops. The kind of rain that spills over the gutters and showers down from the eaves and makes a noise like someone stirring macaroni and cheese with a large wooden spoon. And I sat atop my duffle bag beneath the meager offerings of an awning. The wind-tossed mist of the storm licked my face and soaked the hems of my coveralls and beaded on the oily leather of my steel-toed boots. My hair was sucked down against my skull where the liner of my hardhat had pressed it flat and I was cold inside and out. But my feet were warm in the boots and a smile of sad resignation creased the emptiness of my weary face.

I loved those boots almost as I loved the Colonial Williamsburg cottage that sat next to the creek in Auburn, nestled in the shade of the oaks and weeping willows. Schlumberger had asked a lot of me and they’d sent me out into some pretty harsh climates, into cold and desolate regions of the continent to do hard and harrowing jobs, but they had sent me out with those boots. And I loved those boots the way a man loves a good horse or a good dog. And the oil-field is no place for a horse or a dog or even a man for that matter. It’s cold and dangerous and lonely and exhausting. Three hours or three months, you never knew how long they’d need you on a job. It could be mid-afternoon, it could be 2:00 AM. You’d find yourself in the cab of a 4x4 dually pick-up, the thundering fuselage of a chopper, or the nauseating fish-and-diesel-exhaust-scented confines of a rocking crew-boat. They’d drag you off to another rig where’d you’d arrive exhausted and disoriented with that hollow feeling in your stomach like your first day of kindergarten. With the ringing in you ears from the helicopter engines or the droning in-boards. You had to shake hands with red-eyed strangers who had to invade your personal space to be heard over the din of the drawworks and diesel generators. They always looked so old and sad and desperate and you could tell that they were sizing you up, praying that you would deliver, hoping against hope that you would take the night toure straight out of the chopper so they could sleep for the first time in seventy-two hours. And there you would stand, alone in the mud and machine-grease-caked interior of an MWD shack, your hardhat cutting into your forehead, the strap of your duffel bag digging into your shoulder, feeling the gritty moisture of three-day-old sweat and grime beneath your coveralls. You always seemed to be on the interminable spearhead of a forty-eight-hour sleep deficit and you always felt like crying in those first fifteen minutes. But then the adrenaline surges through you and the excitement and challenge of the situation makes you sharp and confident. And you always had those boots and they were with you at every job. They carried you through the snow, the mud, and the bullsh!t and no matter how cold or how alone you were, your feet were always warm down inside those boots and sometimes, your heart would sink to join them when the tears rolled hot down your cheeks in the darkness and the blowing snow, when you’d stand in the lee of the derrick and stare east-south-east as the horizon began to glow, knowing you’d give anything, even the boots, to kiss your wife’s warm cheeks as she sleeps soundly in that cottage a thousand miles away.

I would be kissing those cheeks in less than four hours and the thought made me smile.The rental car office opened promptly at eight and in less than half an hour I was on the road, headed straight to Auburn. I had it all planned. I was going to scatter rose petals along the floor of the cottage and up the stairs to the loft and I was going to wait for her to get off of work and come home and I was going to sing Fly Me To the Moon to her from the railing over the fire place. I was exhausted but happy and I rehearsed, singing along to Frank Sinatra all the way up I-65. I couldn’t wait to hold her in my arms, to hear her breathing in the darkness, to hear the swishing hum of the ceiling fan, to smell the familiar scent of her fabric softener in the sheets, to the see the rain sliding down the dormer windows outside. I knew the marriage was suffering from my work, but I had to pay the bills and I never doubted Tracy’s commitment. I always assumed that we were braving a rough spell and things would mend as soon as I got her moved to Lafayette where I was stationed.

I arrived in Auburn and parked the car in the parking lot at the Brooks, an apartment complex across the road from the cottage. I was still wearing my steel-toed boots and my cover-alls were unzipped and I had the arms tied around my waist. I had my duffel-bag slung over the shoulder and keys in hand and I was trudging through the clover and dandelions under the crape myrtles when John, my neighbor, waved and jogged up to me. He was as lanky as ever, carrying himself like a handful of twigs. He flashed his trademark sly grin and he was barefoot as always, clad in ratty cargo shorts and a polo-shirt with his wispy, college-boy haircut with bangs that tickled his eyelashes when he blinked. We stood in a patch of dandelions. The breeze caused the crape myrtles to rustle and the sunlight peppered the grass through the leaves and I could smell the horses. John tried to make small talk but I could tell that something was bothering him. He was usually so laid back. This wasn't the easy-going, cheerfully-cynical guy that I'd had a beer or two with every other evening while trading home-improvement ideas and commiserating over how sh!tty a job the home-owners' association was doing with the landscaping. He slapped a mosquito that had landed on his neck. Our eyes met and he knew what I was thinking. "I don't know if this is harder for you to hear or for me to tell…" he said solemnly, his thick southern accent floated away on the breeze as he stared down at the dandelions. Somehow I knew exactly what he was going to tell me and for the first time, I realized that I'd been preparing myself for that moment for a long time. And I don't know how I did it, but I managed a gracious yet sad smile to set him at ease and make it easier for him, to give him the impression that I knew what he was going to say. He kept starting over, trying to get it out the way that he wanted to and he was right, it was painful to watch him tell it.

I'd always liked John, but in that moment, I loved him like a brother. He could so easily have stood aside and watched me slip ignorantly into cuckoldry. He could have looked the other way as I became the laughing stock of the town. But he knew that he would've wanted someone to do this for him if he were in my place. And he knew that it was wrong for a man to stand by and watch another man suffer silent humiliation at the hands of a wayward wife. He didn't want to be involved and yet his respect for me as a man and as a friend had driven him to confront me. My jaw was set and I inhaled deeply as I nodded. "I'm not sayin' anything , man…just what it looks like to me is all…he shows up almost every night and he stays late….sometimes she leaves with him and she takes a bag with her…" I was processing his sentences in fragments, over-clocking my brain as I labored to piece things together, trying to smile. I felt sour inside like something had curdled and rotted there and my throat felt thick and constricted. My toes curled tightly inside my boots as I struggled to cling to what composure I had left. "He's a wily little redheaded mother f&%ker. You could kick his ass easy." John had noticed the new thickness in my arms and neck. I didn't hear him, though. My mind was processing every last detail, zipping back and forth through the seven years that I'd been with Tracy. What had I done to deserve this? I just couldn't make sense of it all but as the crape myrtles whispered in the breeze, I began to see things from a broader perspective.

My father had always told me that life wasn't fair, that it was hard and often cruel. But theretofore, life had been far more than fair. Aside from the West Point incident, at least. Life had been benevolent and pleasant. I spent my childhood on a tropical island, I was athletic, talented, well-educated, and I came from a family that had never tasted divorce or death. I had graduated cum laude with a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering. I was twenty-five and already buying my first home. I was an easy target for life. Deep down inside, I'd been cringing for the whole of my adult life because I knew that things were too good, that life had been too good to me. Because I knew that life wasn't good to anyone. Somehow my happiness and success had escaped her malevolent gaze and I'd known this all along. I'd known that when she did turn her soulless puta-eyes on me, that I'd be paying up with interest. And I'd been waiting the way a child waits for an influenza shot, the way that a besieged city waits for the attack in the darkness. Knowing that the longer I waited, the worse it would be. And here I was, standing in the dandelions as my world came crashing down around me. And it wasn't grief or desperation that flooded in, it was relief.

I'd always wondered how I'd manage under circumstances like those and as I stood there, something inside me hardened as the seeds of bitterness were planted. I swallowed hard as the first tendrils of the numbness wrapped themselves around my guts. And I was saying to myself: So this is how it will happen, this is how I will pay for my carefree years. My mind was frighteningly clear. I remember being keenly aware of myself and being keenly aware of the fact that this was where I'd find out what I was truly made of. I'd read eye-witness and autobiographical accounts of the men who charged out of the Higgins-boats and onto the beaches at Normandy amidst the inclement clouds of whistling lead and shrapnel. How they knew what they would face even before they stepped from the relative safety of the boats and into the harrowing carnage of the massacre. And how their courage prevailed over their fear and, with tongues and throats parched with the thirst of combat, they marched stoically up the beaches as the guns above burped the flaming lead and shat the scalding brass. I’ve seen paintings of charging infantry where the faces were alive and you could see the fey slough of imminent death in all of the pallor, yet the features were stern with conviction and determination. Or the faces of men who stood before the gaping muzzles of the firing squads. Some would beg in the squalor of their incontinence, some would flinch, squandering the last of their breath on "Hail Marys" and "Our Fathers." And then there were always the ones who had courage that was tempered with conviction, who’s countenances where brazen and unflinching, even in the light of strobing muzzle flashes and staccato reports, even as the volley announced its arrival with the dull, thudding splat of rippling flesh and rupturing organs. And in their eyes was the gleam of absolution that never wavered, even as they fell, and it lingered, even after death, shining from beneath the waxy glaze. I had always revered and admired such courageous men and I had always wondered if I had the substance and resolve to stand in their places and face my fate with the same stoicism and mental clarity. And as the bees ravaged the dandelions, I was scheming behind the ramparts of my mind and I was smiling out loud in the euphoria of my lucidity. I was shocked and almost frightened by the coldness and clarity of my thinking. Yet giddy and almost gleeful with how empowering the inner tranquility was. My mind was as sharp and crisp as the morning air in an aspen grove with freshly fallen snow. John’s voice crescendo-ed as it pulled me from my introspection. "Does Tracy know you're here?" John scratched at a mosquito bite on the back of his leg. "No," I replied at length, "no…"

John saw the fire in my eyes and he new what was to come. "Your guns. You should move them all over to my place until things cool off." I nodded in agreement. He’d read my mind. I knew that this composure and coolness would dissolve when the full might of my wrath was brought to bear on that damned son of a bitch. And I went hot, through and through as the rage began its nasty work and I struggled hard to subdue it. I didn't know much about fighting but I knew that the rage would only encumber me, that I needed my wits about me, that it was imperative that I retain my composure right up to the moment when the grizzly business of working this kid into a mild coma commenced.

Rage is a funny thing. It cripples your aptitude for strategy. It is your foe right up to the fight itself, and then it is your ally. Rage is how the average man can kill with bare hands. This is why rage is an essential quality in a berserker while it is poison for generals and officers. You’ve no sense or self-restraint once you are drunk with it and you are capable of horrid things if you don’t make allowances for this. Thus I breathed deeply and pulled the coldness back in. And I felt as if I were having a thousand thoughts at once, and a strange tranquility accompanied this intellectual ubiquity. I felt very fine and unhurried, though I knew that there were a thousand ways to proceed. I could not fail to own the sadistic glee of vengeance. The trickiness resided in the choice of which way to go about gaining the satisfaction of milking the sweet teats of masterful destruction.

I felt as I had on the day, when my noon scouting found me squatting in the woods next to the upturned peat of a fresh scrape. So fresh that the gritty soil was still moist and you could smell the earthy scent of decomposing leaves and pine needles. He was big. The tracks were wide and deep and the dewclaws had left their marks. It was noon and the sun was high. I had seeped into the clearing like a fog, moving through the pines like a mist. Gliding silently in moccasins drenched in doe urine, unannounced and unnoticed. I stood confidently and skirted the clearing like a specter. It was noon and the sun was high. His tracks had led me into the clearing and I saw where they would lead me out. In an instant, his entire life had flashed before my eyes, everything that he had ever seen, tasted, smelled, felt, and heard. His favorite hickory groves, the musk of his first rut. And in an instant I extrapolated, seeing him materializing in the clearing at dusk, his roving obsidian eyes scanning incessantly, his wet twitching nose probing the shadows. But he would not see me because it was noon and the sun was high and I had time to make the killing perfect. I had time to move downwind, to coalesce with the gnarled roots of an old oak. I had but to wait, to brave first the numbness, and then the terrible aching of stiffness when you dare not move a muscle, when you feel that the wiggling of your toes in your moccasins is an indulgence. I had but to sit with the hardness of the oak in my back, watching squirrels pass at arms length, as time and nerves left me second guessing.

It was now noon on the first day of May and the sun was high and I had time to make the killing perfect and I smiled sadly at John, because this was certainly harder for him than it was for me. "I’ll get the guns," I said distractedly as I patted him on the shoulder, and walked towards the cottage. He turned and watched me. The world was suddenly so vivid and full of textures and scents and sounds. The cracks in the driveway slithered through the fragmented concrete. Each little pebble begged for my attention, offering themselves to a mind that was frantically grasping for something to cling to. The driveway seemed to stretch on forever and I walked slowly, wishing that it would, not caring if it did, studying the cracks and jutting aggregate as if I were seeing them for the first time, the way I was now seeing the world.

Zoe’s tail thumped violently against the sides of her cage. I could feel her smiling at me from behind the bars. "Daddy! Daddy!" she was saying. But I counldn't look at her. If I paid her any mind, she would piss her self dry in her excitement and regardless of the measures I took to clean it up, Tracy would doubtless be suspicious when Zoe failed to piss in the yard when she walked her that evening. Ignoring her was almost more than I could bear because I loved her the way I would someday love my children. The cottage smelled differently and though my name was on the mortgage, it was not mine anymore. It was not my home and as I gathered my guns, I forced myself to focus on the task, careful not to look at the bed, my marriage bed, careful not to go into the bathroom, afraid of what I knew, like a child afraid of what he may see if he peers out into the darkness from the safety of his covers. But I saw her thong on the carpet at the top of the stairs and something hot hemorrhaged in my chest as I wondered if he had taken it off of her, if he had pushed her back onto the bed, what had been my bed, in what had been my house. So you stand there and try to shrug it off, trying to swallow the scratchy throbbing lump, blinking away the tears, feeling your chest caving in on your heart.

With the guns safely stashed in an upstairs closet, I sat cross-legged in the floor of John and Shay’s living room, listening to John shout at their pair of over-fed miniature pinschers who, it seemed, had been bred to bark and shit incessantly. And between invectives, John would turn and describe to me the things he had witnessed over the course of the previous months, always adding apologetically: "Just sayin’ how it looks to me is all." "Last time you were here, you hadn’t been gone longer than twenty minutes before he showed up. He’s over there almost every night. You should wait and see, wait for that little red-headed mother f&%ker." Every time that he referred to Tracy in both proper and pronoun-al form, you couldn’t miss the disgusted tone in his voice or the grimace on his face. It was like watching my dad talk about Jacques Chirac. And the more he told me, the less ardently I pleaded Tracy’s case in my head. And as compelling as his testimony was, he would always pause and add musingly: "Maybe it’s nothin’." But he would immediately see how silly that sounded and would retract. And as the afternoon wore on, the weight of high drama descended upon us as the bleak realization that action of some sort could not be avoided, that things were bound to escalate. And as we sat pensively, laboring diligently to keep the awkward silences at bay, John began the first of what would be more than a score of confabulated retellings of his account. And I, unable to cope with the waiting, began to engage in a relentless session of calesthenics amidst John’s rambling and the interminable yapping of the min-pins. All the while, Shay sat across the room; hugging me compassionately with her eyes as she talked in fragments, seemingly to herself, apologizing for the treachery of certain subgroups of her gender and saying among other things: "No one deserves this." And "You have never treated her badly, Josh."

By and by, we (John and I) settled on a course of action that we were confident would culminate in the visceral satisfaction of some good old fashioned facial reconstruction, wherein I’d dish out retribution with extreme prejudice upon that miserable wretch’s frame. He was built like a porcelain feather and would dissolve readily beneath my fists, for after John described him to me, I instantly made him out to be one of Tracy’s co-workers. A twenty-one year old infant of a boy, whose mother still dressed him and wiped his ass when he shat. In the course of the coming year, my reflections would lead me to the obvious logic behind Tracy’s choice of such an effeminate and juvenile lover, videlicet her deep-seeded hatred of men and her insistence on choosing partners whom she could easily manipulate without laboring to first castrate them. She had, after all, plucked me from virginity as a mere boy and up until this day, she had enjoyed the Margot Macomber existence that my subservience had afforded her. She had married a boy, but she had a man on her hands now.

And as dusk came, John stood silently by the window, having abandoned recollection. The dogs had grown silent except for the occasional yap. Shay had fixed me a turkey sandwich which I accepted gratefully despite the loss of my appetite. And I consumed it mechanically, knowing that I needed the fuel. And I took some Gatorade with it, chewing half-heartedly, swallowing with great difficulty, for my mouth was parched with the adrenaline. And all the while, John stood before the window, watching and waiting with the impatience and eagerness of a novice soldier who has yet to master his nerves. And shortly after dark, I saw him bathed in the headlights of the old Cherokee as Tracy pulled into the driveway next door. He then turned from the window and sprinted up the stairs to the loft. This, of course, set the min-pins to barking again and in the excitement, the smaller of the two fell off of the sofa and landed on his head; and had the occasion been less grave, it would have been a very funny thing to see. John returned with a pair of two-way radios as Shay consoled the little dog who seemed very pleased with the attention. John could not conceal his smile, and this brought a smile to my face. The seriousness of what was to come could not entirely preclude the almost gleeful thrill of clandestine activity. "I’m gonna go out and have a look," John said, "You stay in here." I protested, insisting that it was dark enough out for me to move freely without detection, but he would have none of it and was even unwilling to allow me to stand in the window. "If she sees you, it’s all over." He said. It was all rather silly in hindsight, that is, the sneaking about in the dark armed with two-way radios and binoculars. All we really needed to do was to wait for the little prick to show. But John had insisted upon vigilance, arguing that the "little twat knob" might only pull up long enough for Tracy to run out and hop in the car with him. Shay stood by and shook her head, doubtless thinking how silly boys were about things like this. And we all talked excitedly in hushed voices, as if Tracy were upstairs or in the next room.

I sat in the living room floor in the dark listening to John’s occasional radio chatter. John had forbade us the luxury of light and had only begrudgingly allowed Shay to turn on the television. I wanted desperately to succumb to my fatigue for I’d not slept in more than thirty hours, but I knew that prince-charming could arrive at any moment and I wanted to be awake when I rushed out to beat the little felch-pump senseless. "She’s in the kitchen… She’s gone into the bathroom… She’s watchin’ TV… She’s…I don’t know what-tha-f&%k she’s doin’…" John’s hushed voice barked from the radio, giving a play-by-play of Tracy’s evening. Meanwhile I rehearsed various scenarios in my mind, imagining myself walking straight through the front door to find Tracy and Monsieur Douche-bag sitting side-by-side on the sofa. Seeing the look first of shock and then of terror on Tracy’s face, and savoring every second of it before pulling up a chair and sitting down in front of them so close that our knees would nearly touch. And saying in a very serious fatherly tone: "Son, do you love this girl? Are you prepared to accept the responsibility of providing for her?…" I don’t remember falling asleep but I remember Shay draping a blanket over me gently and taking the radio out of my hand before whispering into it: "John, get your ass in here!"

I awoke in my face-paint, war-drums throbbing in my head, in my dreams I had slain a thousand men and my thirst for carnage was still unquenched. I had slept for twelve hours without waking. The leather of the sofa was cool to the touch and it squeaked under my weight as I sat up. The silence was blinding and the sunlight was deafening. My senses grappled with the surroundings. The scent of unfamiliar laundry detergent and potpourri was pleasant, but disorienting. The smell of a home that was not mine. I had no idea where I was, and yet I was not at all alarmed. I’d rarely awoken in the same place more than twice over the last three months and the panic of disorientation had long given way to resignation. In my grogginess, I was unaware of the events that had transpired on 01 May. Where were my boots? I had the tightness in my chest to remind me that something was terribly wrong. But this was not an unfamiliar sensation. I always had the tightness when I awoke and when I lay down to sleep. I was well acquainted with the quiet desperation and helplessness of a man who is separated from the woman he loves. The tightness and sourness in the pit of the stomach. I found that I had no smile, that I had learned to cover it with war-paint. And in time, the smile had curdled into a sneer and the sneer glared out at the world from beneath the war-paint.

The hinges on the glass door squealed and Shay entered from the porch with the min-pins underfoot. The events of the previous day came rushing into my mind and I flinched inside. Shay smiled sadly at me. "How’d you sleep?" She had to shout to be heard over the min-pins who had immediately commenced with the surliness. "Great." I replied. And in truth I had. John came staggering down the stairs, his eyes puffy and red from sleep. His hair reminded me of the time my sister made off with the kitchen scissors and made a haggard attempt at giving her Barbie-doll a haircut. He had a contact lens stuck to his cheek. I felt cold and exposed. Where were my boots? Shay disappeared into the bathroom. John retrieved a gallon of orange juice from the refrigerator and began drinking it straight from the jug in big thirsty gulps. He was winded when he lowered the jug from his lips, wiping his mouth on the back of his hand. He shot the yapping dogs a murderous glance. "Shut tha f$%k up." He growled. It was no use. The little bastards were relentless, like a southern Baptist sidewalk-preacher with a bullhorn. John set the jug on the counter and we met at the window and stood shoulder to shoulder, squinting out into the sunlight. John scratched the small of his back. "Nothin happen’d lass night…" John yawned, "the little pecker-head never showed up." "Hmm…" I yawned in answer. Tracy’s Cherokee was gone. The toilet flushed in the bathroom behind us and Shay emerged shortly. "She left for work at ten ‘til ten." Shay said as she shushed the dogs and corralled them into the bathroom. She swung the door shut and suddenly the dogs seemed very far away. John and I turned from the window. In answer to the un-asked question I said: "I don’t know what I’m gonna do…" John stood and nodded glumly as he nursed his jug of orange juice. Shay smiled sympathetically at me. I looked down at the floor and noticed the toe of one of my boots protruding from beneath the quilt that had spilled from the sofa onto the floor. I pulled the boots on and laced them tightly and the tightness in my chest was eased a bit. I excused myself, thanking them both for their hospitality and assuring them that I would be back shortly.

I made my way through the clover and the dandelions. I was weak with hunger and yet I had no appetite. I desperately wanted a shower but the cottage was as good as haunted now and I dared not re-enter. As I stood beneath the crape myrtles, looking back at it, I heard Zoe’s piercing cry of loneliness. John had told me how she cried day and night, sometimes abandoned for twenty-four hours at a time. The lump that formed in my throat was so thick that I reached up to make sure the skin had not split. I blinked back the tears, turned, and ran to the rental car.

Frank Sinatra was still playing when I started the car. I opened the door and vomited in the parking lot. The following hours were spent driving aimlessly around Auburn. I was finally alone, and the grief came in waves. There were moments when my tears were so thick that I absent-mindedly engaged the wind-shield wipers. Eventually, the tears abated and the cold, ruthless, clarity returned. I produced my cell phone from the console and dialed my parents’ number. My recitation came in hollow emotionless shards of shattered grammar as my parents’ listened. "Oh, Josh…" The immeasurable consternation and sadness in my mother’s voice nearly choked me. But I was stolid in my composure and my father and I conversed now solemnly and matter-of-factly as tacticians would on the eve of a great battle. With the facts laid out before us, we knew that the evidence lay mightily against Tracy. "But we don’t know for sure that there’s anything going on." My mother broke in, her voice trailing off as she immediately realized the folly of her supposition. "We DO know what it LOOKS like!" My father said emphatically in a brusque tone. "You may as well be a cuckold, Josh. The shame isn’t lessened any by what has or has not occurred behind closed doors! The fact remains that what she is doing is an outright and asinine show of disrespect! You cannot tolerate this, Josh. You can’t. Here’s what you need to do. You need to sit her down and tell…No. You’re a grown man. I’m not going to tell you what you should do or what you should say, but I will say that you cannot tolerate this behavior and still call yourself a man." I smiled inside at this and I felt the hotness in my guts again. I knew I would deliver on this one. I would own my father’s pride and my own honor before sunset. Verily, Tracy had written the first chapters of this volume, but I would write the final chapter and the epilogue and in so doing, I would secure my honor and self-respect.

My anger burned greatly against Tracy and I knew that this would not do, that what I had to do must not be done in anger. I knew that I had to be above reproach in this, that I had to rise to the occasion and conduct myself in a manner that would leave no room for justifiable retaliation. Tracy had never tolerated criticism or rebuke. She could not abide even the insinuation of wrong doing on her part, to the degree that one could justifiably conclude that she believed whole-heartedly in her being entirely incapable of doing or being wrong in any and every matter. She would, as a matter or course, engage in an impressively thorough dissection of her accuser’s character until she succeeded in exposing some flaw or foible, however severe or benign. And armed with these findings, some of which were entirely contrived on occasion, she would ravage the accusing party’s character and reputation until she was satisfied that all attention had been drawn from her own imperfections. And when she had no other recourse, she would put forth the most nauseating and childish display of self-righteous indignation that I have ever seen. In fact, this arrogance would in later months provoke me to the extent that I would tell her flat out that she needed to wake up and smell the sh!t because it was hers and it stank tremendously. Thus I knew that when I confronted her, I needed to leave no room for her to justify her actions by citing the injustices in mine. With this in mind, I realized that the public annihilation of her little boyfriend was quite out of the question for the time being. He would not, however, escape my wrath for I would deal with him some years later.

I concluded the conversation with my parents, promising to stop by and see them on my way back to the wharves. No sooner had I flung the phone into the passenger seat, than it rang; startling me. I recognized the number instantly. It was the satellite phone in the MWD logging unit that was stationed on the TODCO 200. I answered hesitantly. It was Josh, the lead MWD hand who had remained on the 200 during the casing break. "We’re scheduled to pick up tools at midnight he said." I could hear the sudden pronounced growling of heavy machinery in the background. The door to the logging unit had apparently been flung open. The static jingle of dragging chains, the grinding din of pumps and generators, and Josh’s voice, shouting at someone in the distance. I heard the door slam and then silence. "That was Rheed." Josh said, "He says the boat’s gonna leave the wharves at 0200 tomorrow. Don’t be late." I hung up the phone and drove directly to the cottage.

I turned my key in the lock and rammed the door lightly with my shoulder as I always did because it stuck. Where as before I had moved briskly through the cottage, intentionally keeping my eyes from focusing so as to blur my surroundings in an effort to avoid seeing anything that would jeopardize my composure; I now stood brazenly in the doorway, surveying what had once been my home. The living room seemed darker than I remembered, and the carpet seemed browner. The scent of Downy fabric softener and Febreeze that used to welcome me home was now strange and unfamiliar. The furniture looked smaller and the ceilings looked lower. The room seemed dirty and lived in. But the homecoming at the end of a protracted absence is always this way. Time pulls the stains from the carpet, freshens the paint, mends the upholstery, and sands the blemishes out of the woodwork; leaving the room pristine in your memories. And you see the little things as if for the first time. I stared at the wall clock as if I’d never seen it before. I could remember the day that we purchased it and brought it home. But the second that I hung it and made it straight, it had effectively ceased to exist. The candles on the mantle, the stitching on the lamp shades, the galvanized metal bucket next to the fireplace. All the little things that I had looked at daily but never seen. The room was crowded with forgotten details, yet it was empty of the welcoming and familiar charm that it had once possessed.

It felt as if I had no right to be there and I moved cautiously as if anticipating an ambuscade. Zoe’s tail thudded loudly against the walls of her little crate and she pawed the metal bars of the door frantically. She cried out in panic and desperation. Pleading for my love and attention, believing whole heartedly that she had done something to disappoint me the day before. Not knowing or understanding why I had ignored her. And she had so missed her daddy, missed him every day, sniffed under the door of his closet, and slept on his pillow; and when his scent left that, she had been forced to sustain herself with memories of days when she and her daddy had swam in the pond, chased squirrels at Keisel Park, and played doggy-tackle in the living room amidst Tracy’s half-hearted scolding. And now here he was and no matter how she cried and called to him, he couldn’t hear her. Oh but I could hear her and it had broken my heart more than she would ever know. And now I ran to her and threw the cage door open whereupon she came at me like a speeding bulldozer and we rolled backwards onto the carpet. She was shaking uncontrollably as she lay on my chest, whimpering hoarsely and licking the tears from my face. Her big brown lab-eyes swallowed me whole. "Shhh. Daddy’s here." My voice cracked and the words shattered painfully in my throat. I didn’t want to be sobbing but she was all I had now and her love and loyalty vastly exceeded any I could expect from any person on the planet and this realization was immensely moving. Man’s Best Friend simply could not do her justice. She was a runt half-breed and yet God in his infinite compassion and benevolence could not have blessed me with a more noble and selfless companion.

So you're standing in the shadows of your incipient cuckoldry, laboring valiantly to suppress the emotions that are now fighting for your attention. This isn't your home anymore and the air is heavy and hard to breathe, thick with the stink of adultury. And you don't hate her yet. The hating comes later, with the alcohol and sleepless nights. For now, all you have is the hurt, the deep visceral aching hurt of betrayal as your imagination begins to paint blurry pictures that amount to something like him being inside of her. And you blink wildly, wide-eyed. The tears are scalding your cheaks and you can smell the tepid saltiness in your nostrils. The ceiling begins to droop and the paneling in the walls is bleeding into the furniture. No more clean lines, just a congealed mass of soggy colors. And somewhere in the sopping bog that used to be your living room, your hand finds the doorknob and you spill out onto the porch. The chunk of polished granite is lodged in your throat and your guts draw themselves into a cold solid knot. But you have nothing to give other than the mouthful of acrid bile that blends with your tears as you wretch over the railing into the holly bushes. It's a gentle spring breeze that dries your tears now as Zoe consoles you with her whimpering. And as your head clears, you begin to smell the hot, sticky, sweetness of the mimosas and the honey suckle. The freshly cut lawn is bruised with the shadows of the oak and maple canopy where the little gypsey sparrows flit about in the branches. And then you're slumped on the stairs with Zoe scrambling to be in your lap as she licks your face. A few deep breaths later and you're cursing yourself for the foolishness. You sit there, exhausted, watching the little brown ants march out of the cracked mortar between the bricks. You watch them lay seige to your boots, you watch them climb the dusty leather and disappear beneath the hems of your Carharts. And then you feel the first set of mandibles ratcheting into your flesh. And then another and another until your shanks are on fire. But you cock your head to the side and stare off into space dreamily. You're discovering for the first time that there's something so soothing and pure in the palpability of physical pain. But as the delerium ebbs, you rise and stamp the ants off of your legs. "You can't stay here." You say to yourself wearily.

I could not stay there and I had no desire to stay there. Instead, I longed for the relative safety and familiarity of the oilrig. The crew-boat that would carry me to the TODCO 200 was scheduled to depart from the wharves in Theodore at 0200 the following morning. Being onboard that boat was suddenly a matter of survival. I had to be back on the TODCO 200, the iron colossus that stood mockingly beneath an endless sky and towered over the vast moat of the choppy gulf, surrounded by nothing but water and sparsely scattered oil-wells for as far as the eye could see. There I would be sheltered from my grief by the grinding rage of heavy machinery, the hollow shrieking ring of drill-pipe being tossed about in the derrick amidst a hazy mirage of diesel exhaust. Yes, I would be safe there where the air was thick with the shrill screaming of steel on steel as the chains jerked the tongs. Where I would have that tickling sensation in the nape, knowing that at any second, a chain could break or a cable could snap or a pipe could blow, and I’d be nothing more than a thudding 150 pound slab of lifeless meat marinated in brain-matter. Yes, there was always the tickling sensation in the back of the neck, the same sensation that makes you shutter when you stand at the edge of a cliff or the roof of a tall building and something inside has the audacity to suggest jumping. The tickling sensation in the cervical vertebrae that says: "Don’t f&%k up or you’re toast." The palpable dread. And then the godlike omnipotence and supreme confidence that well up inside as the fear and dread are consciously relegated to the periphery, leaving behind the cold surgical cognizance of a matador. Thus, out of my grief was born an addiction to the endless rigor and danger of the oil-rigs. The rewards were tripartite. The exhaustion numbed you to the pain of personal tragedy, the nearness of death was strangely comforting; and then, if you emerged from the experience unscathed, you would never fear any man or circumstance ever again for as long as you lived. Thus the crew-boat became my Valkyrie, and the rig became my Valhalla. I stood catatonically in the yard, looking down at the cellphone in my hand. It seemed so small and useless, so pointless, like an emptied Pez dispenser. I had her on speed-dial. She was a mere two keystrokes away, five minutes by car, twenty on foot. And yet the distance between us, that the wedge of her unfaithfuless had cloven, was so hopelessly vast that I wondered if we even existed in the same universe anymore. Compulsively, I pressed "3" and "Send." My left hand nursed my throbbing temples, my right hand pressed the phone to my ear and somewhere in that other universe, I could hear her phone ringing. The sun slid languidly behind the maple tree and little crepuscular beams of light painted the front of the cottage with a leopard print of dancing shadows. I turned slowly, still massaging my temples with my left hand. Zoe was hunched up, extruding a gargantuan turd in John's yard amidst a diatribe of muted min pin barking. Zoe was smiling derisively at her yapping audience. The surly little wretches were standing on their hind legs, jumping up and down behind the glass door as if they were skipping rope. John was standing behind them with a sad expression on his face. Our eyes met briefly and awkwardly. And then, in an effort to escape the awkwardness, we both focused on Zoe, who was just concluding her sordid business on his lawn. Our eyes laughed in embarrassment and when he turned back to me, I grinned sheepishly and mouthed the word "sorry." "Hello?" Her voice was strained and hollow. My eyes dropped away from John's and I turned away. This was the tone she took with telemarketers; edgy, skeptical, consternated. I had called her from my cellphone and the significance of this had not escaped her. A call from the rig's sat-phone meant I was marooned on the groaning iron beast, far from the wireless conveniences of civilization. A call from the cellphone meant that I was at large. She was already on her heels and I had not even said a word yet. A twinge of tachycardia accompanied my sense of invincibility. "You should come home. We need to talk." My words echoed in the cold expanses of the void.

"Well, I'm sorry, but someone's got to live in Philly." Dr. Shannon interjected sarcastically, shrugging his shoulders and lifting his palms. Everyone in the class laughed. I couldn't remember what he was explaining, but his illustration involved driving down the Jersey Turnpike to Philadelphia. Partial pressures or some such nonsensical notion that undergraduates are loth to contemplate amidst the endless hedonism of the freshman experience. None of us had ever been to Jersey or Philly and more than half of us couldn't find either on a map. But it was fashionable to laugh at jokes like these. Every one of us just got caught up in the act, the existentialism of what we thought was adulthood. Being entertained by a "hip" professor whose salary was being paid by the collective "Rich Daddy." Not a care in the world, as we wallowed in the debauchery of the perpetual collegiate weekend. Faux-adulthood cultured in the bliss of ignorance. Or so it seemed. I distinctly remember being acutely aware of my insecurity and hearing not mirth, but terror in the laughing voices of my peers. Dr. Shannon had said something that was very funny but we had no idea why it was funny and we were terrified of the notion that the whole of the world lay beyond the state line. The anachronistic simplicity of Southern life had left our social flanks exposed to the wolves. And as hard as we tried to howl, all we could manage was a chorus of pathetic bleating. My palms were sweating and my ears were hot. Daddy's currency could buy us a sememster of CHEM 102, but it could not buy us an ounce of self-respect or class. But I did have self-respect and I had seen the world and it killed me that I had stooped so low in the act of laughing at a joke that I did not get. And all in an effort to keep up appearances before those bleating phonies. And in that moment, from the conflagration of my shame and conviction, rose the phoenix of my confidence. I vowed in that moment never to fear the unknown and yet never to do battle on terrain that was unfamiliar. I would stick to what I knew and I would know what I stuck to. And now, I would stick to my manhood, my self-respect, and my righteous anger. I was upstairs in the loft when she arrived. I heard the key in the deadbolt. Slow hesitant footsteps. I could hear her laying her purse down carefully on the table. She cringed as the jingling of her keys betrayed her. She stood pensively on the carpet, scarcely able to breathe. She knew I was there. Somewhere. I moved like a whisper to the top of the stairs. I had occupied myself with yet another masochistic session of calisthenics and my hulking lats, delts, and traps eclipsed the light of the small dormer window. The skin-tight Under Armor shirt hugged every chiseled ridge in my abs and pecs. Black tear-away Addidas sweat pants. The rigs had made a man out of me. She had never seen me like this. The boy she married was gone. She had a man on her hands now. A supremely confident and terrifically powerful man who would not be castrated. I was

Francis Macomber only I had no intention of leaving the Mannlicher in the truck with the treacherous little Memsahib when I went to kill this water buffalo. No I was determined to dominate every angle of this encounter.

Her footsteps in the carpet, the timid wary gait of a hunted animal. She appeared on the landing below. She lifted her chin defiantly with great effort, but she could not lift her eyes as readily. And slowly, very slowly, her gaze crept up the stairs, faltering like an over-burdened pack mule. The juggernaut that was my silhouette towered menacingly above and even in the shadows, my eyes must have burned like phospohorus. A sharp cry of terror grew lodged in her throat, restrained there by foolish pride. The terror in her eyes was there but only for an instant. It was quickly masked by cold hatred as she labored to despise me. Where is your Mannlicher, Margot? Where is your Mannlicher? The cold diabolical laughter in my eyes ran its icey fingers down her spine. She staggered backwards, afraid to turn her back on me. I choreographed my advance to match her retreat, pace for pace, and together we moved like suspended aggregate in the icey bowels of an inching glacier. She fell backwards into the chair in the corner and I pulled one of the iron-framed wicker chairs up and sat down in front of her. The afternoon sun shown through the red drapes, painting everything in shades of bergundy, illuminating the little particles of dust that gushed through the gap between us. I sat close, our knees almost touching, so close that I could see the striations in her pupils. Thus we sat with our words tumbling into the expanses of the void that was wedged between us. I knew that she was lying, though a part of me tried desperately to believe her. Her eyes were murderous and cold. There was rage in place of the fear and I hated her for it. And behind the rage and insolence was a haunting emptiness. I wondered where she was and I knew that where ever it was, it was a dark place. Her eyes were cold and blue like ice just below the waterline. "That's bullshit!" Her voice was shrill and venomous and I knew that she was screaming inside. And her shamelessness made me hate her. It tempered my resolve. And I assembled my sentences with the care and precision of a watch-maker. Calmly and cooly, I said my piece. And she bucked and spat in the stocks. My composure was too much for her. Where is that Mannlicher Margot? I trembled inside with sadistic euphoria.

Alive! Alive at best; which, I suppose, is fantastic under such circumstances as mine were then. I don't know what warrants the recitation of this, a most egregious, account of my saga of sorrow. Fascinating the realization of cuckoldry is for a man; he is, on one hand, fueled by righteous anger and shrewd confidence and, on the other hand, he feels like a pathetic marionette in the greater tragedy that is life; and I submit to you that it seemed that every string had been severed and that I lay then wholly lame and flacid upon the stage of my existance. That the juxtaposition of such diametrical sentiments can exist within a man's psyche, is profound indeed. I looked into her eyes with all of the intensity that I could muster. "I don't care if it's innocent or not. I know only what it LOOKS like and it looks as if I'm a cuckold. Do you know what a cuckold is?" She did not respond. Her icey gaze seemed fixed on everything and nothing. My eyes were a furnace then. "A cuckold is a man whose wife is unfaithful," I continued. "A woman who doesn't care if her husband LOOKS like a cuckold is just as dispicable as the woman who MAKES one of him and I won't stand for either." My voice was as cold as a corpse in the frost. And then, softly and sincerely, I said: "I love you, Tracy, I do. And I know this hasn't been easy and I'm sorry. I'm going to give Schlumberger my notice and I'll be home in two weeks and unless you are committed to honoring our marriage vows as I am, don't be here when I return." Her eyes widened slightly and her pupils dilated in a nearly indescernible flinch, registering the involuntary acknowledgement of my words. I stood, letting my lats spread like ominous wings, I flared my sternocleidomastoid like a cobra, and my jaw set as though it had been chiseled from granite. "Look at me." I demanded coldly. Her eyes climbed fearfully and I knew she lacked the fortitude to gain the summit. "You need time to think about what I've said so I'm going to leave. Perhaps I'll see you in two weeks." With that I turned and left without another word. The words had piled up between us like an indomitable mound of rubbish in a narrow hallway. We were worlds apart then and the microcosm that comprised the intersection of our universes was such a hoplessly thin one. And yet it was a ravenous and infinite void that would consume all of the time we would and will never spend together. I felt like a giant as I forced myself to trudge over the heartache. I wanted to feel nothing save the exhilaration of being a man.

I don't remember much of the ride back to Mobile or the taxi-cab ride to the wharves. I paid the driver with cash and as the cab crunched its way out of the gravel lot, I stood with my bags at my feet in front of a little shack in the sepia cone of a flood light. It was midnight and I was early. The Mr. John had not yet arrived and I was dreadfully tired. My deep forlorn sigh and frosty breath disolved in the darkness. There was the muted thickenss in the night air that lets you know that you are on or near the water. And then, of course, the gentle lapping of the water itself against the stanchions, the frothy gurgling and dull rumble of inboards idling, and the cyclic creaking of the mooring lines going taught as the boats bob in their berths. The scent of creosote and the machine-grease smell of heavy machinery. This was a dangerous place full of tension and grinding machinery, unfamiliar even in daylight.

Machine grease. I'll never forget that smell. The first time I smelt it was as a young boy when my uncle placed me in the seat of the old green John Deere tractor. I was a mere toddler. And I looked so small and silly in that yellow seat with its cracked, sun-damaged upholstery. My excitement was mixed with terror. As a child, I had harbored a largely irrational fear of being run over by cars and trucks; large vehicles of any type, really. This paranoia manifested itself in my hiding behind trees and running up porch steps when cars passed by the yard. I would run, imagining that they were bearing down upon me like wild mindless beasts. It was like running up stairs to bed after the downstairs lights are out. In particular, I was dreadfully scared of bull dozers and steam rollers. These I watched with great interest and enthusiasm from a distance, but I never had the desire to go anywhere near them. And there I sat on that monstrous machine with those great ravenous tires only inches away from me. I can only compare it to the time I sat on the elephant at the circus. I did not like the looks of him at all and I made no small effort to inform my mother of this. As I sat on that yellow seat, my hands were pressed together and shoved between my thighs and my shoulders arched inwards so that they nearly touched under my chin. Anything to maintain the distance between myself and those enourmous tires that hulked menacingly on either side of me. The visible evidence of my consternation must have been comical because my uncle laughed a great stentorian laugh so that his eyes shined with mirth and affection. For I sat motionless, petrified. Only my eyes moved and they did so timidly as I surveyed the tractor and glanced pensively at my guffawing uncle. In my dread, my olfactories locked onto the smell of the machine grease that oozed from the tractor's orifices. To this day, that smell produces the tickling sensation at the base of my skull. That same tickling sensation you get when you turn your back on an enraged man and you anticipate the blow to the back or your head as you walk away.

There I was with the crunchy gravel under my boots and the tickling sensation in the nape. But I was no longer afraid. Pensive certainly, but not fearful. And what I would give to exchange the despair and turmoil of adulthood for the silly fears of a small boy. The scent of the bay drifted in on the breeze. It smelled like vinegar and salt potato chips. A host of flood lights illuminated the wharves and held the darkness aloft like a canvas tent. Beneath were the islands of crates, barrels, and stacks of splintery pallets; all encrusted in pelican and gull shite. The rusted tusks of a derilict fork lift jutted from behind an old shipping container in the shadows. And beyond were the wharves with their splintered planking, littered with coils of steel cable and thick manilla rope. And the enormous iron cleats that always reminded me of anvils. The Seabulk Wisconsin sat in her berth, her halogen flood lights bathing her 146 feet of clear deck.

I sighed again and shouldered my duffel bags. The shack's wooden porch groaned under my weight. I had no idea whose shack this was or what purpose it served. But shacks always have that parochial charm that advertises a warm bed and a bowl of porridge. The screen door screached on its hinges like a house cat getting an enema. I tried the tarnished brass knob hesitantly. The door opened and I stepped inside. Damn. No warm bunks or potbelly stoves. Only a dusty pea-green linoleum floor and brown wood-grain paneling on the walls. Nautical charts and weather-advisory print-outs were tacked to the paneling, all were brown like the pages of an old book. The room was lit by an old desk lamp that sat on the floor in the corner. Aside from a cheap wooden table on the left wall, the room was empty. There was the sour smell of sweaty men that had become so familiar to me in places like those. I detected another more familiar scent and only then did I notice the old chocolate lab. He lay in the corner with his chin flat on the floor between his paws. Big doleful eyes stared up at me, droopy jowls spread out on the linoleum. He was the kind of dog that would sound like Eeyore if he could talk. "Hey, old man." I said softly. He never lifted his head. His sad old eyes only blinked as he sighed. I walked to the table and relaxed my shoulders, allowing my bags to fall to the floor. I removed my therma-rest mat and unrolled it under the table before lying down on it and pulling my fleece over me like a blanket. I set the alarm on my phone for 1:45 AM and let my head fall back onto the mat. I heard the old lab stirring and I heard his claws tap-tap-ing on the linoleum as he approached. I made a double chin on my chest, stared down over my nose, and watched as he walked over to me and plopped down against me with an umph and a yawn. The tears welled up hot in my eyes and I cried myself to sleep as I scratched him behind his ears.

Her hair glowed amber in the sunlight and it danced in the wind with her sundress. The air was cool and smelled the way it does in story books. And the sky was so blue that you could taste it if you looked hard enough and so vast that you had to curl your toes into the grass to keep from falling out into it. Her scent mixed with that of the tulips she had cradled in her arm. She looked back at me over her shoulder and smiled as she brushed her hair behind her ear. Her eyes caught the sunlight and my heart faltered like a newborn fawn. I reached out to pull her to me. Darkness. At first my consciousness was confined to the space behind my eyelids. The panic came sharply with a wave of tachycardia. Then my tactile senses flickered to life and the panic disolved as my feet felt the warmth in my boots. I would sigh contentedly as soon as I remembered how. My brain was busy booting up and loading my surroundings. The muffled far-off sound of a diesel engine. My mind cast the sound aside and rummaged through the details for something more significant. Dirty light oozed in through the gaps in the blinds and lashed me to the floor with sepia ribbons. My eyes darted to my bed fellow who stirred next to me. I smiled and scratched him behind his ears. Theodore, Alabama; the wharves, the shack. I fumbled in the darkness searching for my phone. Someone had turned the little desk lamp off. Footsteps on the porch outside. I looked to the door as it swung open to reveal the silhouette of a stout man with a thick beard. The screen door leaned on him like a cheap floozy and he wore the smoke of his cigarette like a turban. He had a voice like a tuba and as he spoke, the glowing orange orb of burning tobacco bobbed up and down where his mouth should have been. The scent of cod-liver oil and terpentine parted my nose hair and made camp on my olfactories. I felt labrador tail thudding repeatedly against my leg and the old dog lifted his head and loosed a whiney yawn.

"You goin' out to tha 200, son?" The silhouette asked. "Yur a smurf aren't you?" The orange orb bobbed with each syllable like the prompter on a karaoke monitor. A "smurf." I'd heard that we were called smurfs, but I'd never been called one before. Schlumberger directional drillers and MWD hands are always issued blue nomex coveralls and white hardhats. It doesn't take much imagination. "Yes..." I replied groggily propping myself up on my elbows and yawning. "Yes, yur a smurf or yes yur goin' to tha 200?" "Yes to both." "Well, you'll be on tha Mr. John. She...He's moored at the south end of the wharf." He said before muttering to himself:"Giving a boat a man's name...that just ain't right." "Thanks" I said as I wiped the crud from my eyes. The lab stood and shook himself and his claws tap-tapped along the linoleum as he strolled out onto the porch past the smoking tug captain. "Humph" said the captain as he let the screen slam behind him. I rolled my mat up and tucked it away in my duffel bag. I felt sour and sticky in my carharts. I guess you never get used to waking up in places like these. I felt so far away from everything that had happened the day before.

A chilly breeze came from the screen door and I wriggled into my fleece and zipped it up to my chin. The vinegar and salt and creosote smell. The air was clamby with the dew and the mist. I collected my bags and squeezed out of the door. A fog had fallen on the bay and the glare of the flood lights made me feel like I was swimming in soapy bathwater. I crunch-crunched across the gravel towards the sound of diesel inboards. I felt the rough planking of the wharf underfoot. The Mr. John was moored with the stern against the wharf. I could only see the aft section of the clear deck, the rest of the Mr. John was hidden in the fog. I trudged down the aluminum foot bridge and onto the deck. The deck's planking was coated with a thick layer of maroon paint and it glistened with the dew. Locker boxes and coils of rope skirted the bulwarks. The Mr. John was a smaller crewboat. Perhaps 100 feet long with a twenty-five foot beam. She...He, rather, had a large flat deck that traveled from the stern to the cabin, a tall two-level cabin with the bridge on top. The hull was painted black outside, the deck and gunnels were maroon, and the cabin/bridge was white. The paint was so clean and shiny, coat after coat had been applied until a bumpy shell of paint had ensconced the flat steel surfaces. The Mr. John's halogen deck lights were blinding in the fog. My stomach tickled as the boat moved beneath me. I took small deliberate steps like a wind-up-robot. The mist parted like theatre curtains as the cabin came into view. I shielded my eyes from the halogen lights as I approached. "Moanin" The greeting came from the shadows near the manway. I squinted in the lights. "Dem lights'll bline ya, kid." The words came as a cackling African American laugh. I smiled. At first all I could see were his ivory-white teeth in the gloom. My pupils dilated as I slid into the shadows. He was a wiry little black fellow with dingy white coveralls tucked into black rubber boots, and a soft-pack of Marlboro red's peeping from his breast pocket. He was Fred, the deck-hand, and oh the laugh he gave when I called him captain. "Awe sheeuh, boy!" He said through his tears "Ah sho as hell ainno cappin!" He had hands like sandpaper, a grip like an iron vise, and a blinding smile like the headlamp on a locomotive. He had flecks of white lint in his curly black hair and it made his head look like a pumpernickel loaf with sesame seeds on top and he smelled the way pumpernickel tastes. "Sheeuh!" He exclaimed once more, beaming from ear to ear. He thrust the manway open and motioned me through. "Shhh." He placed a finger over his lips.

The manway was set high in the aft wall of the cabin so it was like climbing through a low window to get through it. The cabin floor sat lower than the deck so there was a little step just under the manway on the inside of the cabin. This I missed completely and tumbled headlong into a pile of snorring rough-necks who happened to be sleeping in the floor. A sharp protest of grunts and what-tha-hells errupted instantly. I grimaced and rattled off an assortment of apologies like an auctioneer, trying all the while to avoid eye contact. Wasn't quite sure what to do with my hands as I climbed off of them. Didn't want to touch them, but I had to use my hands to crawl backwards. My knee dug into a thigh. "Ouch ga-dammit!" Someone growled. "My bad." I replied. Something about the way he said it made me snicker. "Shit ain't funny, mother f&%ker!" Someone slugged me in the hip. My bags were crowd-surfing and they arrived on the linoleum just as I did. Fred was doubled over with his hands on his knees, tears streaming down his face. "Sheeuh, boy." He squeaked as he shook his head. "Sheeuh, Fred." I said and smiled. This really set him off.

Fred had me toss my bags into a cargo hold on the port side of the manway and then he produced a grubby white binder and made me sign next to my name on the passenger list. He mumbled something about nine eleven and asked to see my ID. "Don' be crawlin' own dem boys no mo." His chuckle came as a whisper and he disappeared through the manway with a mop in his hand.

I turned to face the cabin. With the exception of the dim flickering bulb over the manway, the cabin was dark and as my eyes adjusted, I saw that rows of benches ran from port to starboard like church pews. All of them faced the blank front wall of the cabin and a centre aisle ran down the middle. The low ceiling, unconvincing wood-grain wall paneling, and riveted aluminum trim made the cabin feel like the inside of a camper. The air was dry and very chilly and smelled like a fish market. The snoring and muffled breathing of the men coalesced with the droning of the engines below to produce a soporific hum. The benches were covered with sleeping rig-workers as was the floor beneath and between the benches. I felt that I was being watched. It was like showing up late for mass on Easter Sunday. Everyone is watching to see what you'll do. So I stepped forward praying that there would be room for me in the darkness. I moved with arms out stretched, stepping over and between the sleeping bodies; tottering, as if I were fording a brook on slippery stepping stones. It was a tangled mass of limbs and snoring heads, sheltered by a patchwork canopy of flannel jackets and wool blankets. The hoarse chorus of snores sounded like a pipe organ with laryngitis. My ears burned red in the darkness. My self-consciousness grew with each step. There wasn't room for me. The only clear space was the area around a pole that ran from floor to ceiling. I got down and curled into a fetal position around the pole. The granite flecked linoleum was cold against my cheek and it gnawed on my boney frame with icey teeth. The floor smelled like stale saltwater and offal, but it was clean, really clean. I sighed. It would be a four hour ride to the 200 and my pelvis was already grinding the skin on my hip into the seam of my carharts. I pressed my palms together as if to pray and used my hands as a pillow. But the purring of the engines was transmitted through my knuckles and into my gaunt cheek-bones and my teeth rattled in the sockets. I welcomed the pain as a distraction. My weary mind was running from the thought of her. Running like a lost, wide-eyed child in a funhouse.

The gears of time seemed to have siezed up; and alas, even my tears of agony would not suffice to free them. A sharp hot throb shot through my chest. I clung to the pole for fear of jumping up and sprinting out through the manway, down the deck to the wharves , and on and on away to the north until I could take her in my arms. The tears and snot ran between my fingers and pooled on the icey floor beneath me. I was sobbing. And then the sudden rolling surge as the engines groaned under their load. As the boat pulled away, I felt as if my guts had been nailed to the splintered planking of the wharf, that they were steadily being torn out of my abdomen as we throttled up and churned out into the bay. The roaring engines masked my sobs. Surely the weight of my despair would sink the boat right there in the channel. I cried until we cut into the gulf. There the sound of the swells and bow-waves making war with the hull made for an unlikely lullaby and the sea rocked the iron vessel like a cradle. I sniffed and sucked a few hiccupped gulps of air in through my mouth. The skin on my face grew taught as a drumhead as the tears dried. My breathing grew shallow and I fell into a fitful sleep.

It's always the same, whether you're sleeping on a plane or a boat or in a car. You awake to the voices. Two men conversing in the manway under the flickering light-bulb. Their voices are hushed and muted and distant amidst the engines' purring. You're too exhausted to make sense of their words and you're only hearing the consonants and the stressed syllables anyways. Too exhausted to care. They sound so far away. And you drift back into the blackness behind your eyelids and she's there waiting for you with malice in her eyes.